ON THE SOUTHWESTERN END of the Tohono O’odham Nation’s reservation, roughly 1 mile from a barbed-wire barricade marking Arizona’s border with the Mexican state of Sonora, Ofelia Rivas leads me to the base of a hill overlooking her home. A U.S. Border Patrol truck is parked roughly 200 yards upslope. A small black mast mounted with cameras and sensors is positioned on a trailer hitched to the truck. For Rivas, the Border Patrol’s monitoring of the reservation has been a grim aspect of everyday life. And that surveillance is about to become far more intrusive.

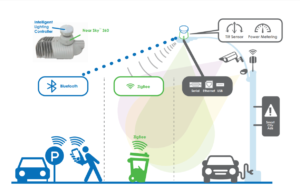

The vehicle is parked where U.S. Customs and Border Protection will soon construct a 160-foot surveillance tower capable of continuously monitoring every person and vehicle within a radius of up to 7.5 miles. The tower will be outfitted with high-definition cameras with night vision, thermal sensors, and ground-sweeping radar, all of which will feed real-time data to Border Patrol agents at a central operating station in Ajo, Arizona. The system will store an archive with the ability to rewind and track individuals’ movements across time — an ability known as “wide-area persistent surveillance.”

CBP plans 10 of these towers across the Tohono O’odham reservation, which spans an area roughly the size of Connecticut. Two will be located near residential areas, including Rivas’s neighborhood, which is home to about 50 people. To build them, CBP has entered a $26 million contract with the U.S. division of Elbit Systems, Israel’s largest military company.

Tohono O’odham people used to move freely across these lands, Rivas says, but following years of harassment by Border Patrol agents, many are afraid to venture far from their homes.

“Now we won’t be able to go anywhere near here without the big U.S.-Israeli eyes monitoring us, watching our every move,” she says.

Fueled by the growing demonization of migrants, as well as ongoing fears of foreign terrorism, the U.S. borderlands have become laboratories for new systems of enforcement and control. Firsthand reporting, interviews, and a review of documents for this story provide a window into the high-tech surveillance apparatus CBP is building in the name of deterring illicit migration — and highlight how these same systems often end up targeting other marginalized populations as well as political dissidents.

The U.S. borderlands have become laboratories for new systems of enforcement and control.

The towers on Tohono O’odham land are part of a surge in wide-area persistent surveillance systems across the borderlands. Elbit Systems of America has already built 55 integrated fixed towers in southern Arizona, which company executives say cover 200 linear miles. According to information provided by a CBP spokesperson, the agency has also deployed 368 smaller surveillance towers, known as RVSS towers, in areas ranging from south of San Diego to the Rio Grande Valley, as well as along parts of the U.S.-Canadian border.

Civil liberties advocates and academics have pointed out the heightened abuses and increased migrant suffering that have resulted from the new state-of-the-art surveillance gear. According to Jay Stanley, senior policy analyst with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, the spread of persistent surveillance technologies is particularly worrisome because they remove any limit on how much information police can gather on a person’s movements. “The border is the natural place for the government to start using them, since there is much more public support to deploy these sorts of intrusive technologies there,” he said.

In February, Congress allocated $100 million for integrated fixed towers and mobile surveillance systems, a sign that the towers may soon expand to new locations.

According to Bobby Brown, senior director of Customs and Border Protection at Elbit Systems of America, the company’s ultimate goal is to build a “layer” of electronic surveillance equipment across the entire perimeter of the U.S. “Over time, we’ll expand not only to the northern border, but to the ports and harbors across the country,” Brown said in an interview with The Intercept. “There’s a lot to be done.”

Read the rest of the story here.